I spent nearly all day yesterday thinking about the Leonardo exhibition. It was an overwhelming experience. There were so many of the artist’s works, all presented with a wealth of new biographical information thanks to the exhaustive research that went into preparing this exhibition. I left, thrilled by what I’d seen but not able to process it all. What was clear was that I’d just spent two and a half hours in the presence of a genius.

So, I suppose my challenge today is to try and do the exhibition justice in this blog and to try and convey something of its power.

Lionardo di Ser Piero da Vinci was born in the town of Vinci on 15 April 1452. He died in Amboise in the Loire Valley in 1519. This exhibition which began in October 2019 marks the 500th anniversary of his death.

Leonardo learnt his craft in Florence as an apprentice to the sculptor Andrea de Verocchio.

Around 1482 he moved to Milan where he worked for Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan. It was in Milan that he painted the Virgin of the Rocks and the Last Supper.

In 1500 he moved back to Florence where he painted a number of masterpieces among them St Anne.

He then returned to Milan where he remained until the election of the Medici Pope, Leo X, in 1513. He then spent 3 years in Rome. In 1516 he left Italy and moved to France at the invitation of the French King, Francois I.

The exhibition is organised thematically, each theme or chapter contributing to a growing awareness of the genius of Leonardo and a more perfect understanding of the artist’s approach to painting.

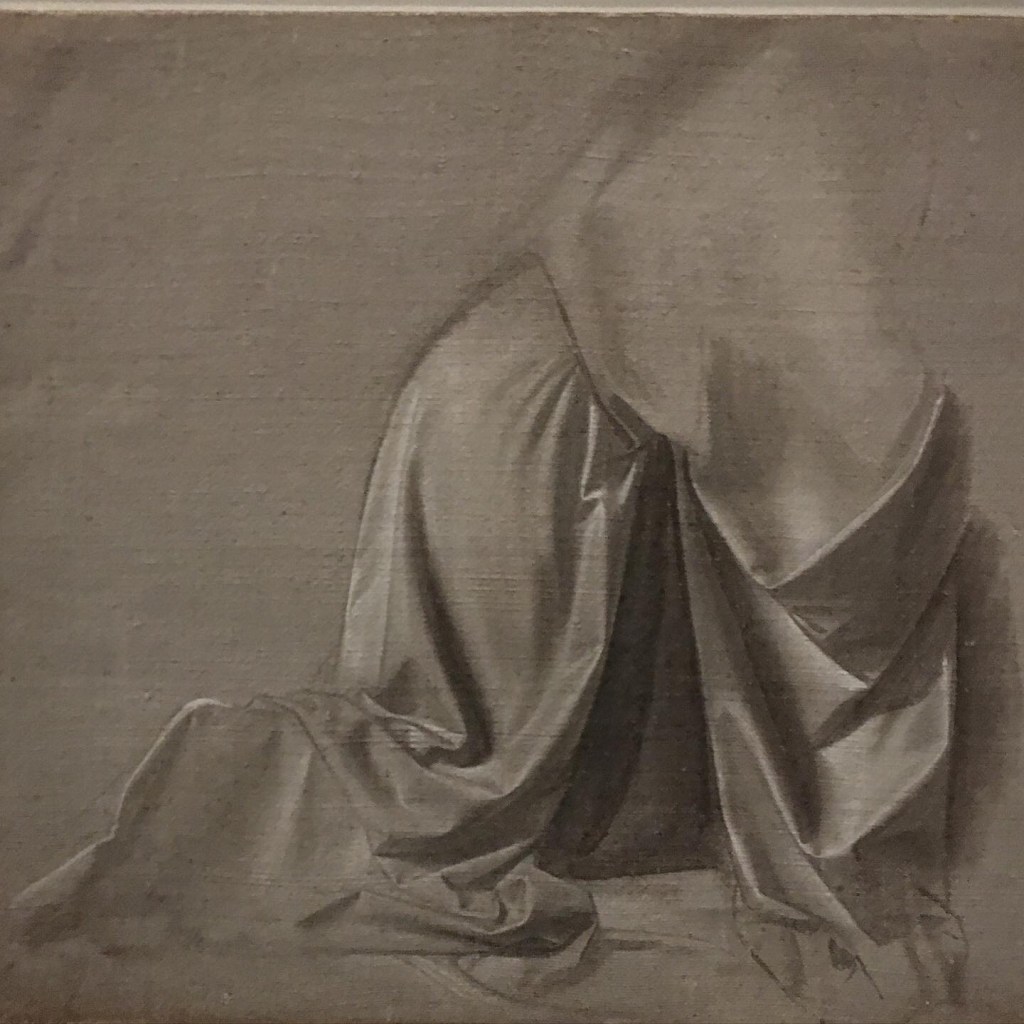

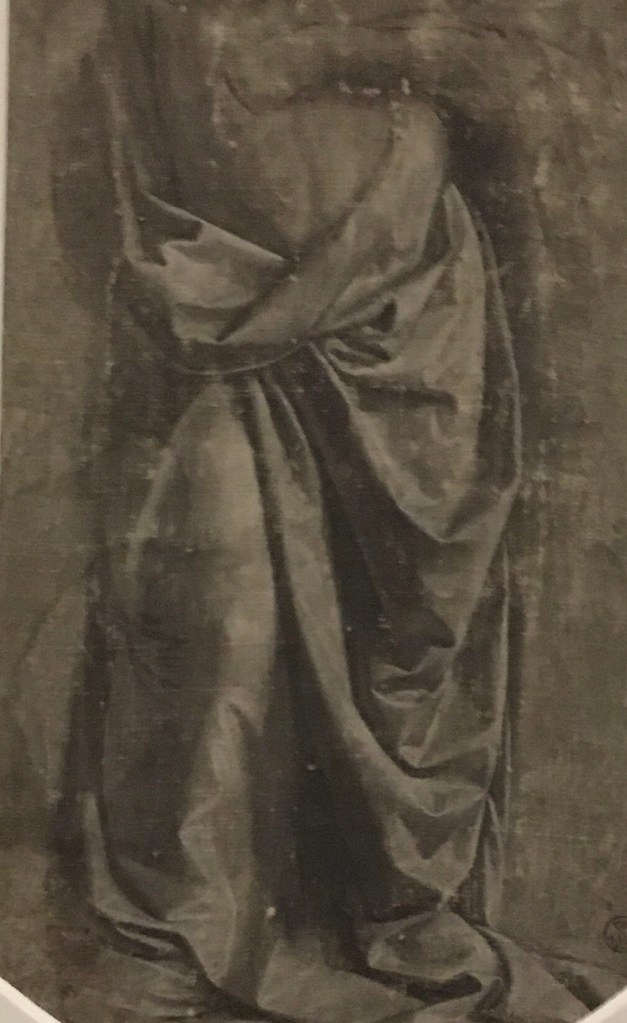

Light, Shade, Relief

The first chapter of the exhibition shows how Leonardo used light and shade (chiaroscuro) for dramatic effect. I loved these drawings, mostly produced while he was apprenticed to Verrocchio. They were almost like little sculptures. I had to look at some of them very carefully to convince myself that the linen on which they were drawn had not been folded. At the end of this chapter I had such an appreciation for how Leonardo mastered light and shade to create both space and form in his paintings.

Freedom

I found this chapter the most interesting but also the most challenging. It was clear that the works I was seeing were supremely powerful. That they spoke directly to the heart and contained universal truths. But why were they so powerful? How did the artist achieve this? Here the accompanying explanations were helpful:

“To grasp the truth of form – which is illusory, being constantly broken apart by an ever-changing world- the painter needed to acquire an intellectual and technical freedom that would enable him to capture its very imperfection”

Leonardo described his approach as ‘intuitive composition’ or ‘componimento inculto’. This gave the artist complete creative freedom. At the end of this chapter I was beginning to get it. There was nothing superficial about what I was seeing. This exhibition was revealing, as if peeling away the layers of an onion, the extraordinary depth in Leonardo’s work.

I think this painting was my favourite. The catalogue explained that it was the first of Leonardo’s paintings “imbued with the dynamism of his componimento inculto.” I was captivated. The way the child concentrates on the flower in his mother’s hand is so perfect, her smile and joy as she encourages him to take it so natural. This a moment of human experience we can all recognise. It expresses a universal truth about our human experience. Then you become aware that the flowers Mary is handing the child are in the form of a cross and this moment of human tenderness between a mother and child becomes achingly poignant. The infant Jesus is concentrating on his own future. By taking the flower he accepts his fate. Mary encourages him, happy in the knowledge that he will save mankind. Yet somewhere in her expression lies the pain of a mother who knows the fate of her child. I was breathless. I could hardly bear to tear myself away from that image at the same time so tender and so painful and yet full also of the hope of salvation.

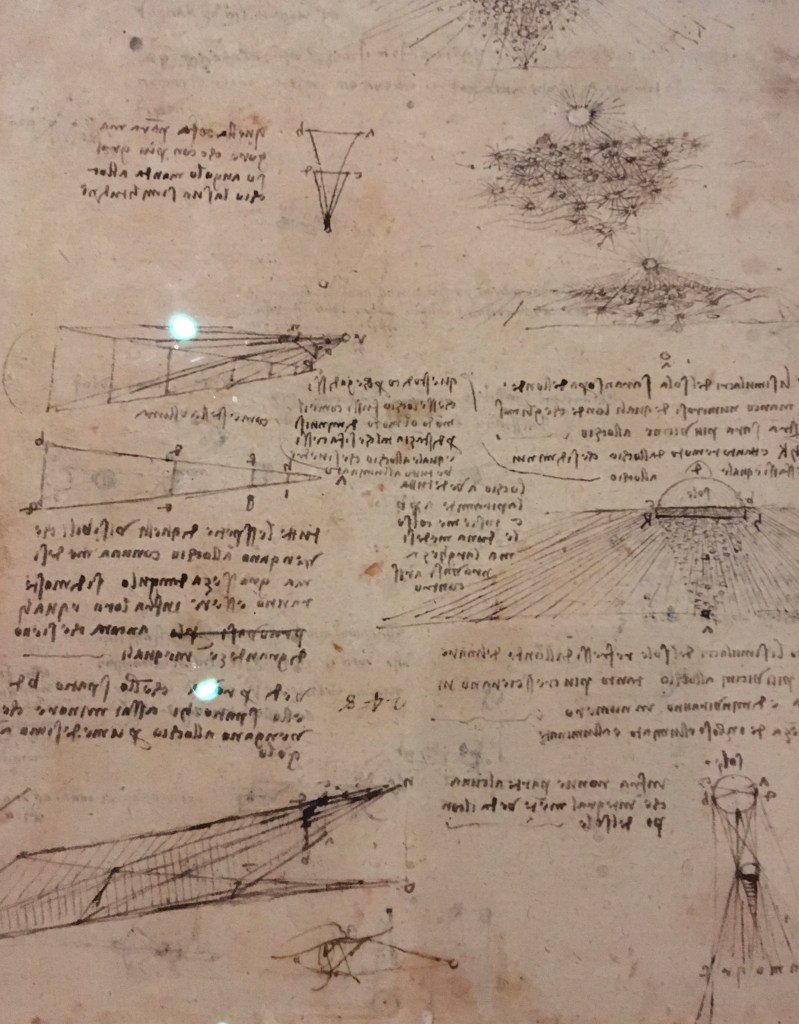

Science

Not being a scientist. I have always been ambivalent about Leonardo’s scientific and engineering studies. Now, however, I understood, that this was all part of Leonardo’s quest for truth.

To discover truth, he needed a full understanding of the world from the inside. Appearances were not enough.

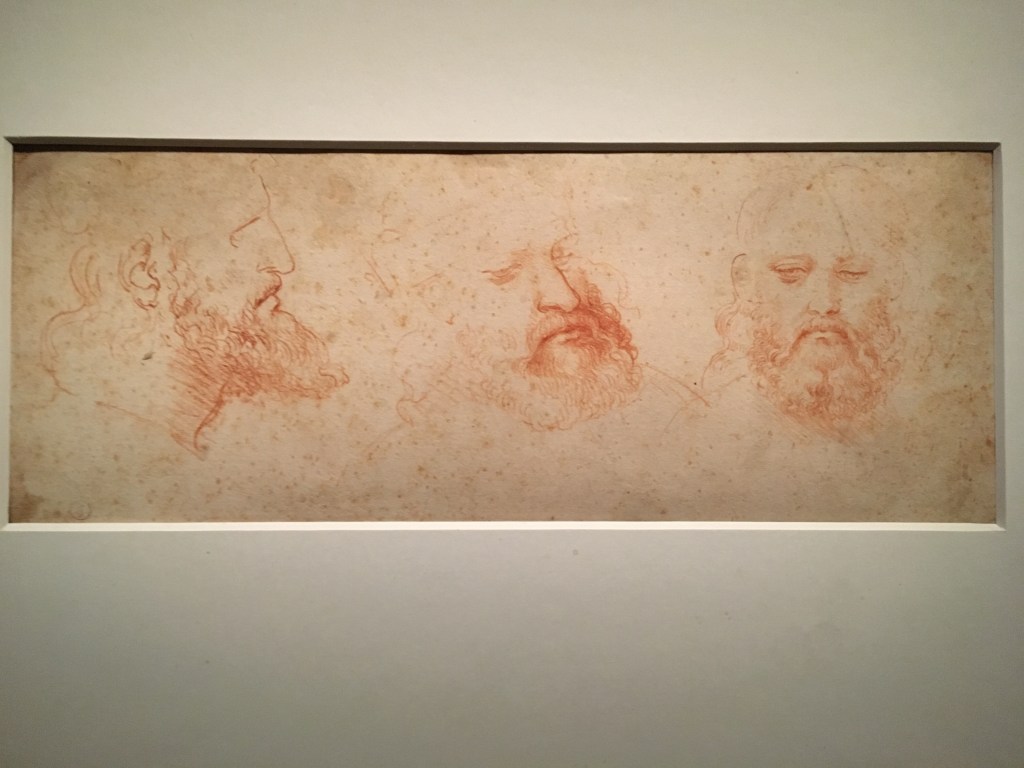

Life

This chapter shows how Leonardo’s constant quests, scientific, technical and philosophical allow him to recreate the world and convey the very essence of life.

Return to Florence

This was a period of political turmoil and strife in Florence and beyond. Leonardo’s paintings reflect this. He returned to the City and painted St Anne and Salvator Mundi, guardians of the city.

Relocation to France

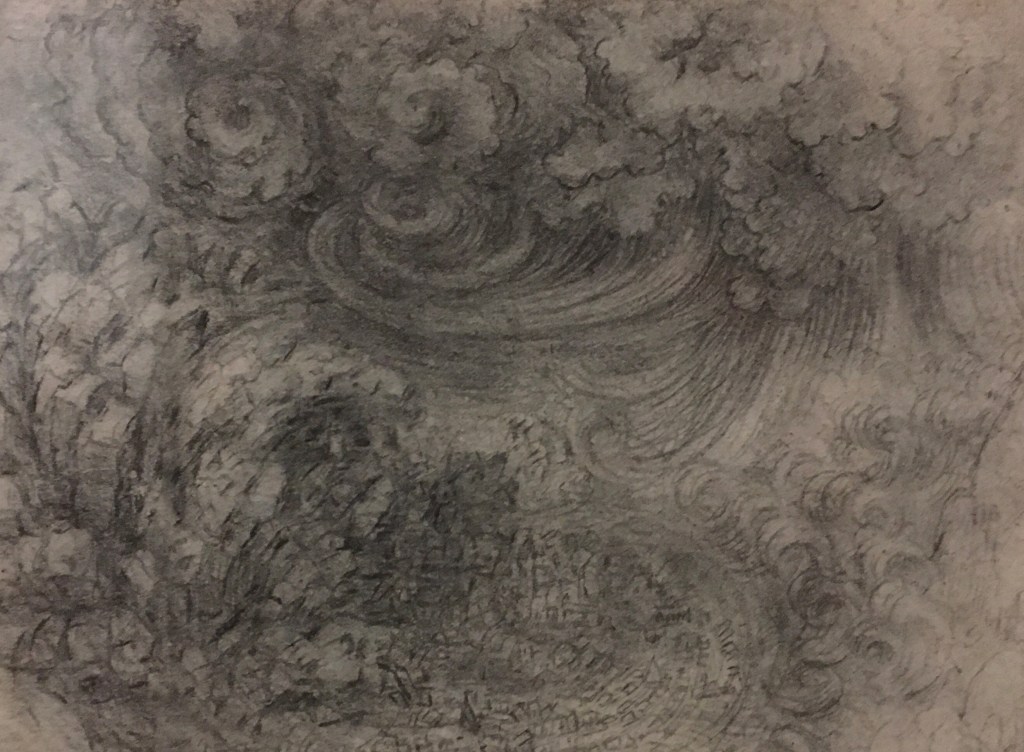

In 1516 Leonardo moved to France where he would end his life. This very brief chapter brings the exhibition to a close. The layers of the onion have been peeled away and the last work on show is this one

This drawing perhaps sums up the overwhelming creative power of Leonardo I was to, coin a phrase, blown away.

This exhibition was a revelation to me. I have come closer to an understanding of the world, of humanity and most importantly of truth. I have been in the presence of genius and I am the richer for it.

Visit my other pages:

What a thoughtful review. Thanks for sharing.

“The painter has the universe in his mind and hands.”

-Leonardo da Vinci

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting way to visit Louvre – so many things on display but you focus on one.

LikeLike

This is a major exhibition. I was reviewing the exhibition not the museum

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh – it isn’t part of the permant exhibition. It is a long time since I been to the Louvre so I didn’t realize it was a special exhibit.

LikeLike

It’s a temporary exhibition to commemorate the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I see.

LikeLike

Beautiful. Thank you, John, for sharing Leonardo from the Louvre. I especially remember his works from Amboise. How much he gave to us!

LikeLiked by 1 person