“And after, no one will really ever remember it. Like the greatest crimes, it will be as if it never happened. The suffering, the deaths, the sorrow, the abject, pathetic pointlessness of such immense suffering by so many; maybe it all exists only within these pages and the pages of a few other books. Horror can be contained within a book, given form and meaning. But in life horror has no more form than it does meaning. Horror just is. And while it reigns, it is as if there is nothing in the universe that it is not.”

The Narrow Road to the Deep North by Richard Flanagan

I hadn’t expected to be confronted by my own family history in Thailand, but here I was standing on a railway bridge above a river recalling shards of conversations that nobody really wanted to have, remembering the fragments of a life that I knew little about.

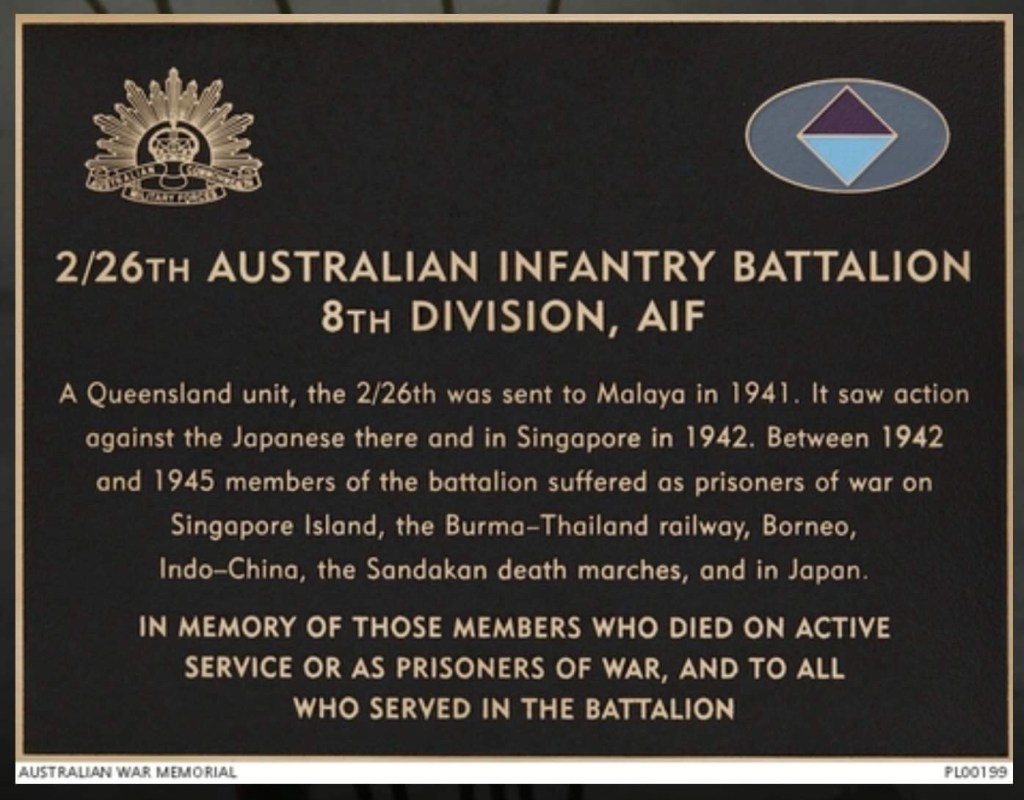

I knew that my great uncle, Jim Smith, had been a prisoner of war, that he had been abominably treated in a Japanese POW camp and that his health had never recovered. He had died young as a result of the damage that had been done during the war. I knew that he had been in Changi prison in Singapore from where many allied prisoners of war had been taken to work on what came to be known as the Death Railway. His sister, my grandmother, had always refused to watch David Lean’s film Bridge over the River Kwai and now standing on that bridge, I suspected my great uncle had been one of those men. I would probably never know for sure, the pain of what happened to him had been too much for his siblings, they couldn’t really talk about him and for us, the younger generation, he was just the uncle who had been tortured by the Japanese.

After the Japanese were defeated in the Battles of the Coral Sea (May 4–8, 1942) and Midway (June 3–6, 1942), the sea route between Japan and Burma was no longer safe for them. New options were needed to support the Japanese forces in the Burma Campaign, and an overland route offered the most direct alternative. With an enormous pool of captive labour at their disposal, the Japanese forced approximately 200 000 Asian conscripts and over 60 000 Allied POWs to construct the Burma Railway.

The conditions were dreadful, disease was rife and the rations meagre, just a small amount of rice accompanied by rotting meat or fish. The men were expected to work all day in the searing heat and humidity with just 600 calories in their bellies. There was no clean drinking water and the food was often contaminated with maggots and rat droppings. Brutal beatings and torture were routine in order to keep to the gruelling schedule. The Japanese desperately needed to supply their army in Burma (now Myanmar). It is thought that one man died for every sleeper that was laid on the railway. As many as sixteen thousand allied prisoners of war died building the railway and tens of thousands more conscripted Asian civilians.

Although I had never met my great uncle, I suddenly felt a powerful connection to him. It was perhaps here that he had suffered the terrible treatment that had cut short his life, it was because of what had happened here that I knew so little about him. I started to walk along the tracks, thinking now about my grandmother and my other great aunts and uncles, people I had known and loved. I walked, my heart full, thinking of the hurt that had started here, trying to imagine the horror and the suffering that had taken place.

Not far from the bridge is the Kanchanaburi War Cemetery, the last resting place for 6 892 Australian, Dutch and British servicemen. Walking among the graves I was struck by how many of them had died during the summer and autumn of 1943. This was a period of intense activity, prisoners would be forced to work for 18 hours a day, suffering from dysentery, malaria, cholera and tropical ulcers. The death toll was horrifying.

Just a month ago I had been standing in the American war cemetery in Normandy. There the bravery of men was celebrated. Men fighting for a just cause, fighting for freedom. Here, the men had died as a result of the most dreadful of war crimes. There was nothing glorious about these deaths.

I felt an ineffable sadness. Sadness for the uncle I had never known, sadness for his brothers and sisters who I had known and loved dearly but who found it so difficult to talk about their sibling. Sadness for all the men lying before me, dead through abuse, disease and starvation. They should have died heroes’ deaths like the men in Normandy.

I stood for a long moment in the graveyard. For the first time in my life my great uncle was more than just a sad story. He was a real man.

Post script

I couldn’t get Uncle Jim out of my mind. When I returned home I vowed to try and find out more about him. There was a bit of detective work involved. Jim Smith is not an unusual name and there were 66 listed in the register of prisoners of war at the Changi prison and 915 listed in the Australian service records.

I didn’t have much information but after a discussion with his niece, my aunt, I had just enough information to find him.

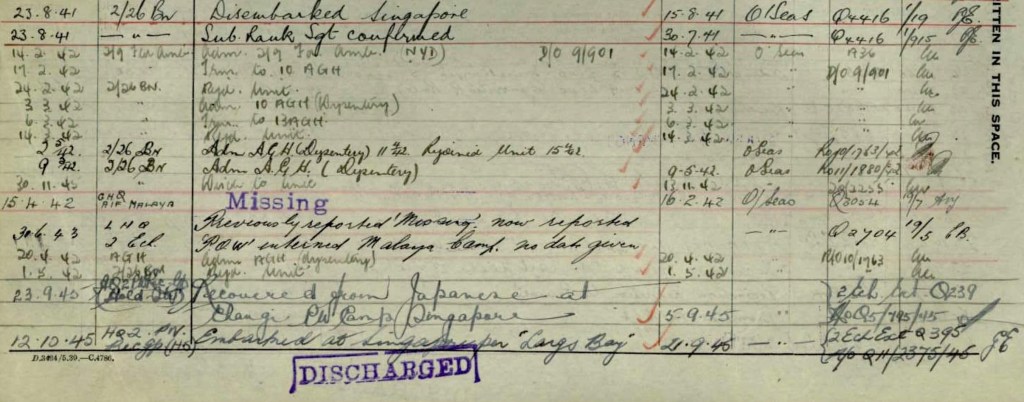

In the records of the National Archives of Australia I did indeed find him. Seventeen pages of his service history had been digitalised.

He signed up on March 2nd 1940. He was made a prisoner of war in February 1942 in Malaya. He was then listed as missing and it may be during this period of 14 months that he was working on the Death Railway. He was recovered from the Japanese at Changi on September 23, 1945 and repatriated to Australia. He lived in very poor health for another 19 years until his death in 1964.

He is commemorated at the Queensland Garden of Remembrance.

At the end of World War II, 111 Japanese military officials were tried for war crimes for their brutality during the construction of the railway. Thirty-two of them were sentenced to death.

Recommended reading

The Narrow Road to the Deep North by Richard Flanagan

Visit my other pages:

How very moving ! Wonderful pic’s ! xxx

LikeLiked by 1 person